①

In most Austronesian shamanistic traditions, the body is believed to be inhabited by numerous souls: a main one (body soul), which is responsible for body functions; and another one that is free to roam around (free soul or wandering soul). Growing up, I often encountered stories describing the soul as an essence that leaves the body in death. Both of these beliefs posit the body as a shell that is occupied—then later on abandoned—and must be attended to just like our living spaces.

②

Rachel Cusk on the parallel between the body and the spaces we nest in, from her essay “Making Home”: “Like the body itself, a home is something both looked at and lived in, a duality that in neither case I have managed to reconcile. I retain the belief that other people’s homes are real where mine is a fabrication, just as I imagine others to live inner lives less flawed than my own.”

③

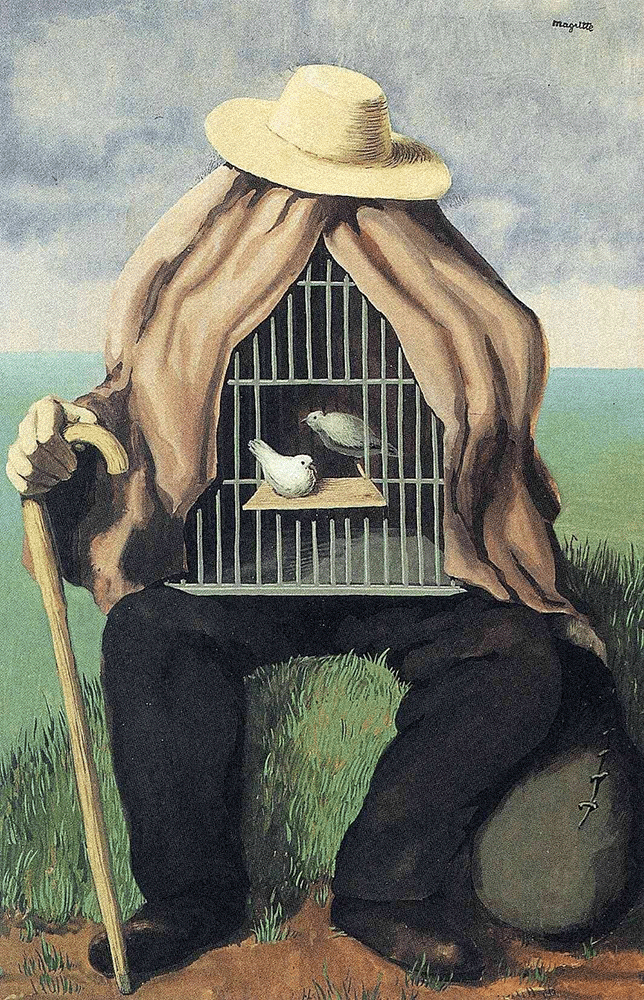

When Franz Kafka said, “I am a cage, in search of a bird.” Like a hollow body, in search of a soul.

④

As within, so without.

Carl Jung’s Bollingen Tower was built in 1923. The idea of it was conceived after noticing a feeling of dissatisfaction despite all the writings he produced and talks he delivered. He felt that he had “to make a confession of faith in stone”. To Jung, the tower represented the maternal hearth.

Four years after the first tower was built, he felt again a sense of incompleteness and decided to add a what would be the central structure. Another four years and a second tower was built. There he occupied a room where he kept to himself and allowed nobody to enter without his permission. He filled the walls of this room with his paintings—his tool of expression for things that cannot be put to words, of things that exist outside of time.

Again, after four years, Jung was restless and desired for an open space so he added a courtyard. In the span of 12 years, the changes that the Bollingen Tower underwent paralleled Jung’s morphing internal landscape.

No further changes were made on the tower, not until his wife’s death. During that time, Jung felt, in his words, “an inner obligation to become what I myself am.” So he added an upper story to the tower’s central section (the part of the tower he associated with his ego-personality), “which crouched so low, so hidden”.

⑤

Another case of outward projection of the inner landscape: In her novel “The Fountains of Neptune”, Rikki Ducornet wrote of a young boy who fell into a coma after accidentally falling off the boat into the river. His coma lasted for five decades, sleeping and dreaming through the two world wars. His waking days thereafter were spent mostly on filling the house with an expansive diorama of the dream world he lived in for years. “As I construct my temples and towers, I am building a bridge between the boy of nine and the man of sixty. I am reclaiming territory. I am making myself a country,” he declared.

⑥

Saint Paul wrote, as if in lament: “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit, who is in you, who you have received from God?” There is no need to search outside of myself, I can meet my god in the cathedral of my own flesh.